The Other Leonardo

Share

500 Years Leonardo da Vinci: In Celebration of the Anniversary of His Death

The works of Leonardo da Vinci exude a hint of chilliness. In his The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, in defiance of mother and grandmother a mischievous Christ child twists a baby lamb’s neck. His angels in both versions of Virgin of the Rocks are of equally enchanting as icily unapproachable beauty – no one should rely on their protection when on the brink of disaster. The Florentine city government intended his mural The Battle of Anghiari as an instrument of patriotic edification and self-education for the political class; instead, Leonardo created – as can be safely ascertained from the preparatory sketches and later copies of the now-lost painting – a manifest of negative anthropology in colour in which war-fevered mercenaries from Florence and Milan angrily collide, intertwine, and slaughter each other. It is a visual exemplification of that which distinguishes humans from animals – namely, the unadulterated desire to kill. The Christ of his The Last Supper in the refectory of the Milanese monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie is going to be betrayed and sold out by a greedy acolyte: a purely human tragedy, not an event of salvation.

In Leonardo’s eyes, man is incapable of redemption; from the laws of nature that bring him forth and then let him wither away again, nothing and no one can release him. On the contrary, there are many indications that the eternal nature will once again destroy this problematic product of its rich palette of creation in some not-too-distant day. Leonardo drew this destruction of humanity through torrential downpours, landslides and tsunamis several times towards the end of his life: accurate in the compilation of the unfettered forces of nature, unrelenting in the delineation of the futile lamentations over a fate fully earned.

This deeply pessimistic view of humanity Leonardo, the writer, expressed unequivocally in his decidedly concentrated fables and riddles. Who cries and laments about the loss of the young who are now being killed and dismembered? The Milanese courtiers, who in response to this brainteaser answered the newborn babies of Bethlehem, were completely wrong – meant were the at least equally innocent little lambs, which are slaughtered and eaten during the barbaric celebration of Easter. Leonardo’s view of nature – that uncreated, omnipresent pulsing force – is inversed: he views it with the eyes of the animals and plants, the creatures that suffer under humanity’s unjustified assertion of being the crown of creation. This alienated viewpoint, which is reflected in the non-Christian messages found in his paintings of Christian themes, was deeply irritating to his contemporaries, as he disavows all apparent absolute truths of the Bible and Aristotle and thus postulates a tremendous challenge: the examination of the laws of nature and thus humankind, that unknown being, for the first time impartially and incorruptibly, without any religious or philosophical whitewashing.

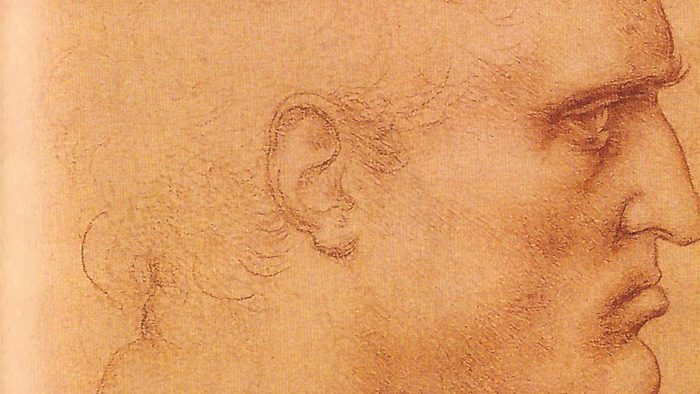

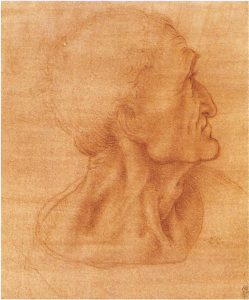

This previously unrecognised duty to humanity Leonardo embraced as his own lonely mission, one which he endeavoured to accomplish through insatiable, curiosity-nourished observation. The thousands of drawings in his notebooks are but the precursor to this cataloguing of the world – painting, for Leonardo, was philosophy: philosophical exploration of nature through the instrument of the drawing pen. For the noble-minded humanistic essayists of the time – for example, Baldassare Castiglione – all that was the ravings of an inerudite gone astray who, through non-performance or (even worse) subversive undermining of the contracted orders, snubbed his contracting clients and thus wasted his extraordinary talent.

Leonardo saw things differently. The study of the nature revealed the other, the sublime, side of the hybrid creature that is humankind: man is the only creature of nature capable of sussing out its laws and with that, his own blueprints.

Leonardo recorded the most important results of this in image and word: the soul of man is his consciousness, that which is fed by the senses, is assembled in the coordination centre of the brain, and generates desires, emotions and actions – and dissipates at death. As a student and copier of nature, man can not only understand its rules, but can also harness it in apparatuses and machines to alter his living conditions – but not himself and his essence.

And thus Leonardo’s inventions, from gyrodynes to super-weapons, are celebrated in the 20th century as ground-breaking and pioneering achievements of modern technique and technology, if not also as anthropological balancing acts and frontiers, with which the unnerving Janus-faced quality of mankind, his creativity and his destructiveness, should be explored. This unflinching journey of exploration we can, after the horrors of the recent past, now understand and appreciate better than ever.

And thus Leonardo’s inventions, from gyrodynes to super-weapons, are celebrated in the 20th century as ground-breaking and pioneering achievements of modern technique and technology, if not also as anthropological balancing acts and frontiers, with which the unnerving Janus-faced quality of mankind, his creativity and his destructiveness, should be explored. This unflinching journey of exploration we can, after the horrors of the recent past, now understand and appreciate better than ever.

Follow us